My exhibition The Coldest War looks at today’s political tensions through the lens of my childhood in East Germany. I grew up in a country built on mistrust and fear, shaped by party leaders who had survived exile in the Soviet Union and returned determined to enforce loyalty at any cost. As historian Katja Hoyer notes in Beyond the Wall, many of these men “had survived the Great Terror under Stalin not by chance but through their abdication of morality” (p. 37). That history echoes in today’s climate, where autocratic regimes still purge their own ranks to secure power and obedience.

My exhibition The Coldest War looks at today’s political tensions through the lens of my childhood in East Germany. I grew up in a country built on mistrust and fear, shaped by party leaders who had survived exile in the Soviet Union and returned determined to enforce loyalty at any cost. As historian Katja Hoyer notes in Beyond the Wall, many of these men “had survived the Great Terror under Stalin not by chance but through their abdication of morality” (p. 37). That history echoes in today’s climate, where autocratic regimes still purge their own ranks to secure power and obedience.

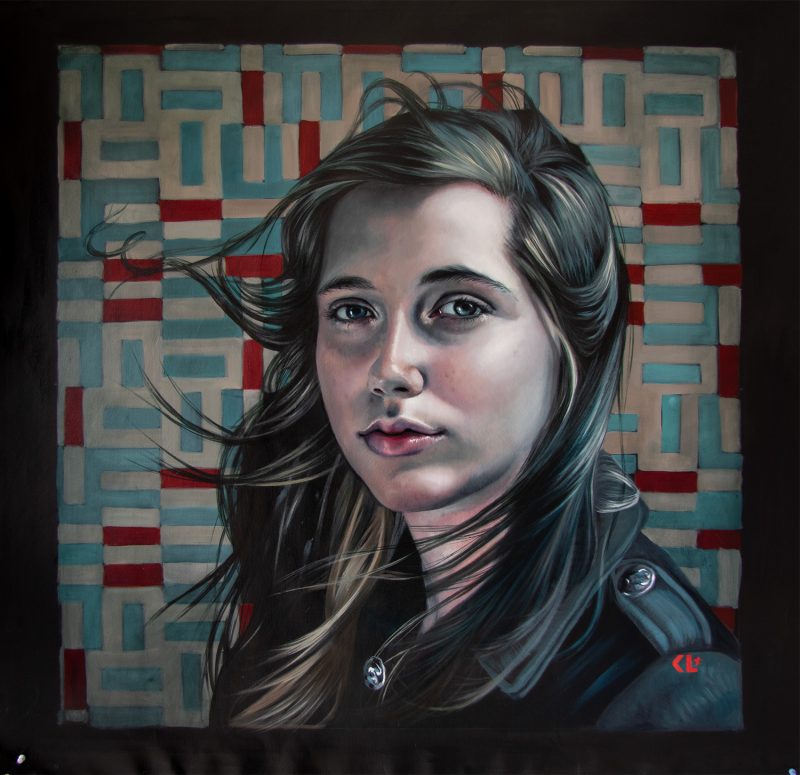

During my childhood, the Soviet Union’s influence touched everything – politics, culture, and even the smallest details of daily life. In my paintings, I reference this by placing my female “war heroines” against backdrops inspired by Soviet Constructivist fabric designs from the 1920s and 30s. In East Germany too, textiles and printed designs were produced by state-controlled factories and design bureaus – reminders of how ideology shaped even fabrics and patterns in the home.

This body of work also elaborates on the trauma of having lived in and survived a surveillance state, where the reach of authority into private life was enormous. As Anna Funder observes in Stasiland, people were reported on “in every school, every factory, every apartment block, every pub.” People’s private spheres were neither private nor free.

Two works also draw on 1970s velour wallpaper, a material that immediately recalls my early childhood. I remember rooms decorated in velvet textures, overseen by official portraits of party dignitaries such as Erich Honecker, East Germany’s calculating General Secretary who held the country in an iron grip.

My family’s own encounters with the Stasi left a lasting impression and sparked my lifelong curiosity about how propaganda works. Through a feminist lens, I paint women who reclaim their gaze and resist being reduced to objects. The Coldest War is my way of confronting the visual machinery of the past while reflecting on its disturbing relevance today.