Artist Statement

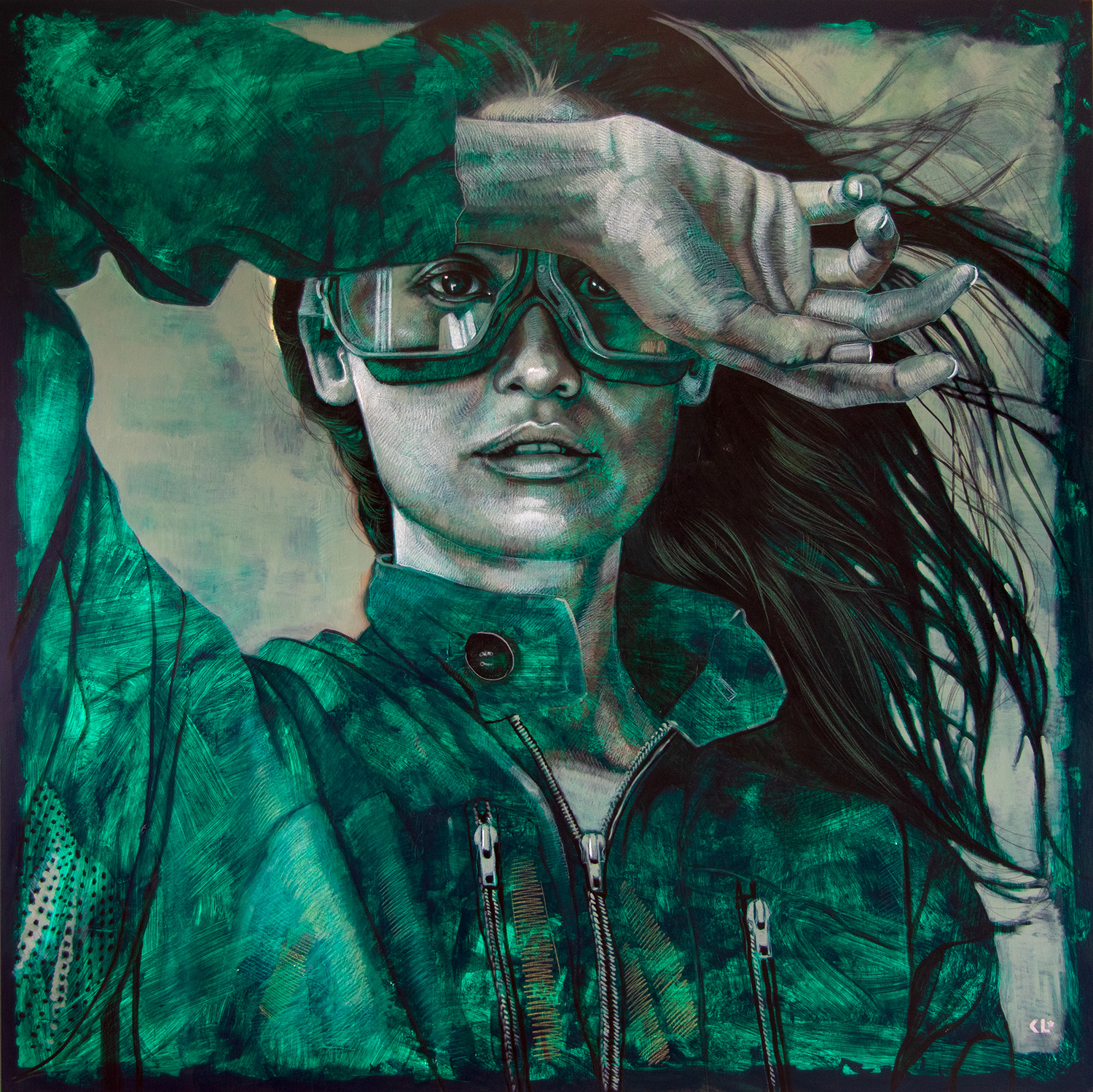

Kathrin Longhurst’s visual language collides with the starting point of her own journey, as a child of the cold-war era, who has been to both sides of the iron-curtain. The contrast between war-propaganda imagery and glamorous promises of the other side of the wall, have been the inspirations of her early works. Longhurst reconsidered war propaganda aesthetics with ‘flying’ female warriors, in place of fearsome male figures of power. Her early works aim to bend the visual paradigm of men and women at war, imposed by the patriarchal power structures of the past. Longhurst’s initial approach is self-observational, rewriting the recent history to empower the idea of a gender-equal future.

‘Volatility’ has been given a new meaning with the arrival of the digital age, as the nuclear fear of the past has been suspended. Longhurst’s interest in the ethics of progression has inspired her to track the footsteps of other women’s journeys, to understand the future-challenges of digital natives. Women’s struggles are an important part of the undocumented history of our civilisation, carrying meaningful information to help analyse the mistakes of the recent history and to avoid any fallacy of progression.

A well-respected member of the Sydney arts community, Kathrin served as vice president for Portrait Artists Australia for some years and was the founder and director of the innovative Project 504, an art space that fosters collaboration between emerging and established Australian artists. She completes her 18th solo show in 2021 and has been a finalist in numerous awards including the Archibald Prize, the Darling Prize at the National Portrait Gallery, the Doug Moran Prize, the Sulman Prize, the Percival Portrait Award, the Mosman Art Prize, the Portia Geach Award, the Shirley Hannan National Portrait Prize and the WA Black Swan Prize. She won the 2021 Archibald Packing Room Prize. Her work is collected widely in Australia and internationally.