Exhibition Essay by Alex McCulloch

“Fading History” February 2016

Portraiture was often a form of propaganda not only during the Cold-War, but in communist regimes such as North Vietnam. This exhibition has multiple visions in that it invokes a retrospective autobiographical stance of the artist whose childhood took place in East Germany before the Wall fell and brought about an annexation of the East into the West.

Kathrin Longhurst deals with her memories of being part of a world where communist aesthetics were at odds with capitalistic values, and the representation of those who fought for the Eastern bloc was necessarily stark and bespoke of solidarity of the group, rather than the individual. Fading History utilises old images of those times and brings them into the present acknowledging that the memories, the values, the solidarity fuelled by ideology are fading—just like a photographic portrait would—the texture embraces a sepia hue whilst the faces fade like the past into the background. Although these artworks acknowledge this ‘fading’, the personal vision of the painter looks at retrieving the past whilst recognising its disappearance from contemporary understanding of a global world. Our world is less divided by capitalist and communist ideologies; other conflicts emerge in these very different times: global capitalism, vast movement of refugees and terrorism closely aligned with religiosity. Longhurst’s paintings embrace a contemporary feminism, which defies any political or religious attitude to disallow a presentation of female sexuality.

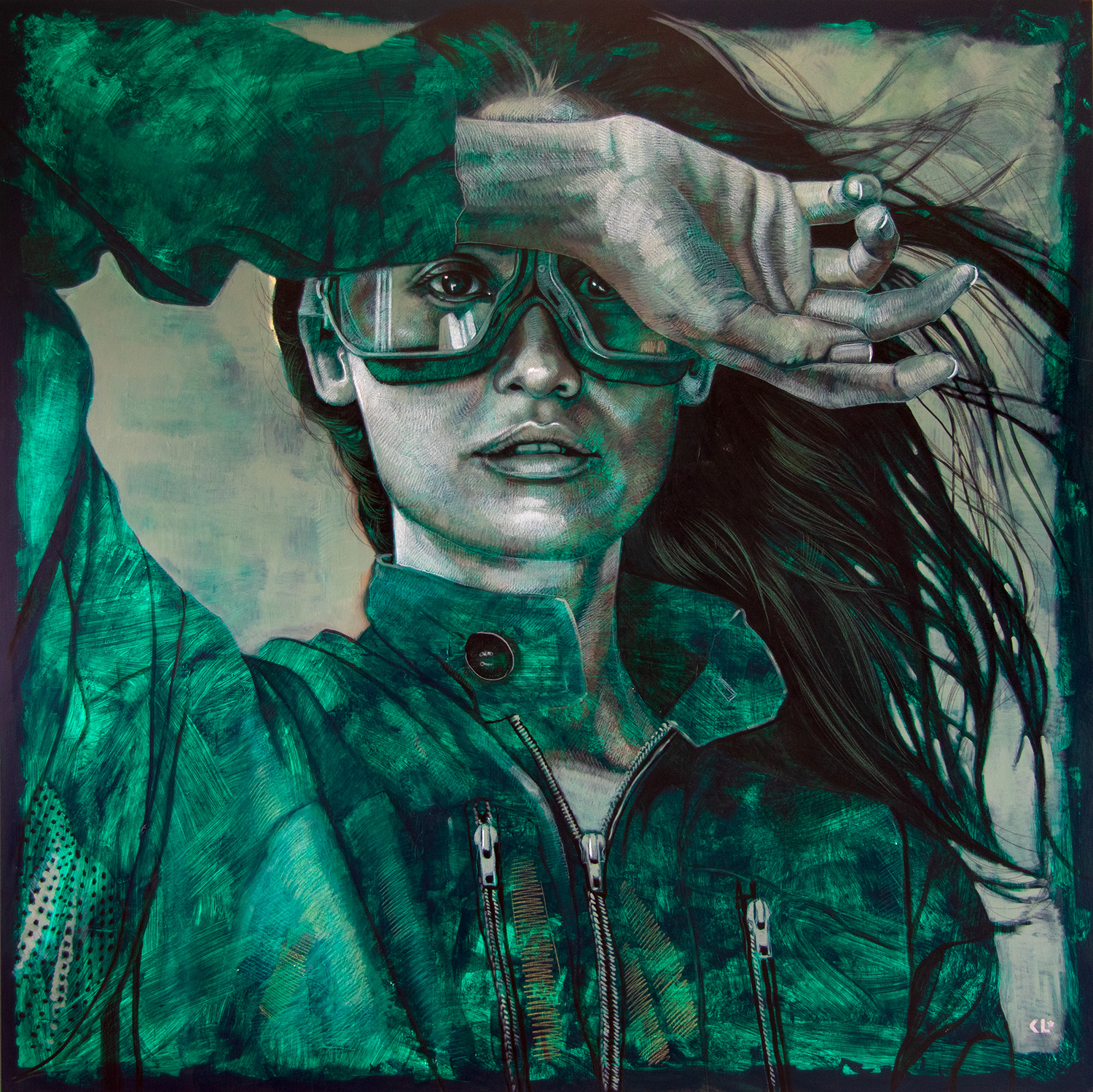

Longhurst employs strategies in her use of acrylic paint, old newspaper images, charcoal, crayons, oil wax sticks and pencil to both keep the viewer at a distance whilst simultaneously seducing him/her into its world of estrangement, and loss. These works capture the last shadows of old attachments. It is as if she wants to make one final statement about these ‘warriors’ who stood for an ideology that is fast fading into history. Yet simultaneously, in some ways consciously (but also unconsciously) Longhurst plays with parody in her orchestration of the past and its propaganda techniques. Whereas soldier propaganda during the Cold War would by design be presented as austere, asexual and assertive Longhurst portraits, wearing the military garb of Eastern Europe, are strongly sexualized with carefully posed half-open glossed lips, moist eyes and the manner of a temptress. They may model the soldier’s uniforms but they are presented as models wearing them and in doing so are defiantly posed as women with appetites and the desire to count as an individual.

The portraits have a limited colour palette with the sepia of old photos, the chocolate of leather and the red bespeaking blood, communism, anger and passion. Longhurst plays with different emotions and standpoints of heroines: they take on the guise of the martyr looking into an untouchable future where a utopia will arrive; a woman sensual but attentive to her role including the right hairstyle of the times when there was access to fashion magazines (so inevitably more 1940’s style rather than that of the sixties through to the eighties); defiant in an overtly sexual way; or looking through her pilot goggles with the partly opened mouth seemingly staring at the viewer inviting them into her Janus-faced world and, then, there is the portrait with the goggles raised to the forehead with a look of alienation and even trepidation yet a mask is worn of fearlessness.

Here is an artist coming to terms with her past. Whilst acknowledging the austerity of living in the Eastern bloc Longhurst also has an ambivalent need to tell its story of potentiality. Part of that story is defiant and critical, part of it wants to acknowledge something great about it but mostly Longhurst wants to give a female representation that subverts the suppression of the energy, sexuality and potential of the female soldier. This is parody at its best and a close analysis of the works shows a fascinating texture in the use of materials. The artistic process was, in itself, wrestling with the questions of what was lost and what was gained during the Cold War for people in the East during the ‘war’ and long afterwards when they were annexed and beaten into a submission.

These portraits tell a complicated story of an attempt to catch the last of the artist’s memory, as much as Longhurst’s re-invention of a time that now has lost significance in world movements.