Exhibition Essay by Sophie Parsons

“Heroes and Villains” November 2014

Growing up in East Berlin ‘behind the iron curtain’, Kathrin’s access to glamour was strictly limited, she longed for ‘pretty dresses and pretty things’. Her paintings recall this love of luxuries formerly forbidden, while her female figures challenge varying definitions of feminism through their combination of strength and desirability.

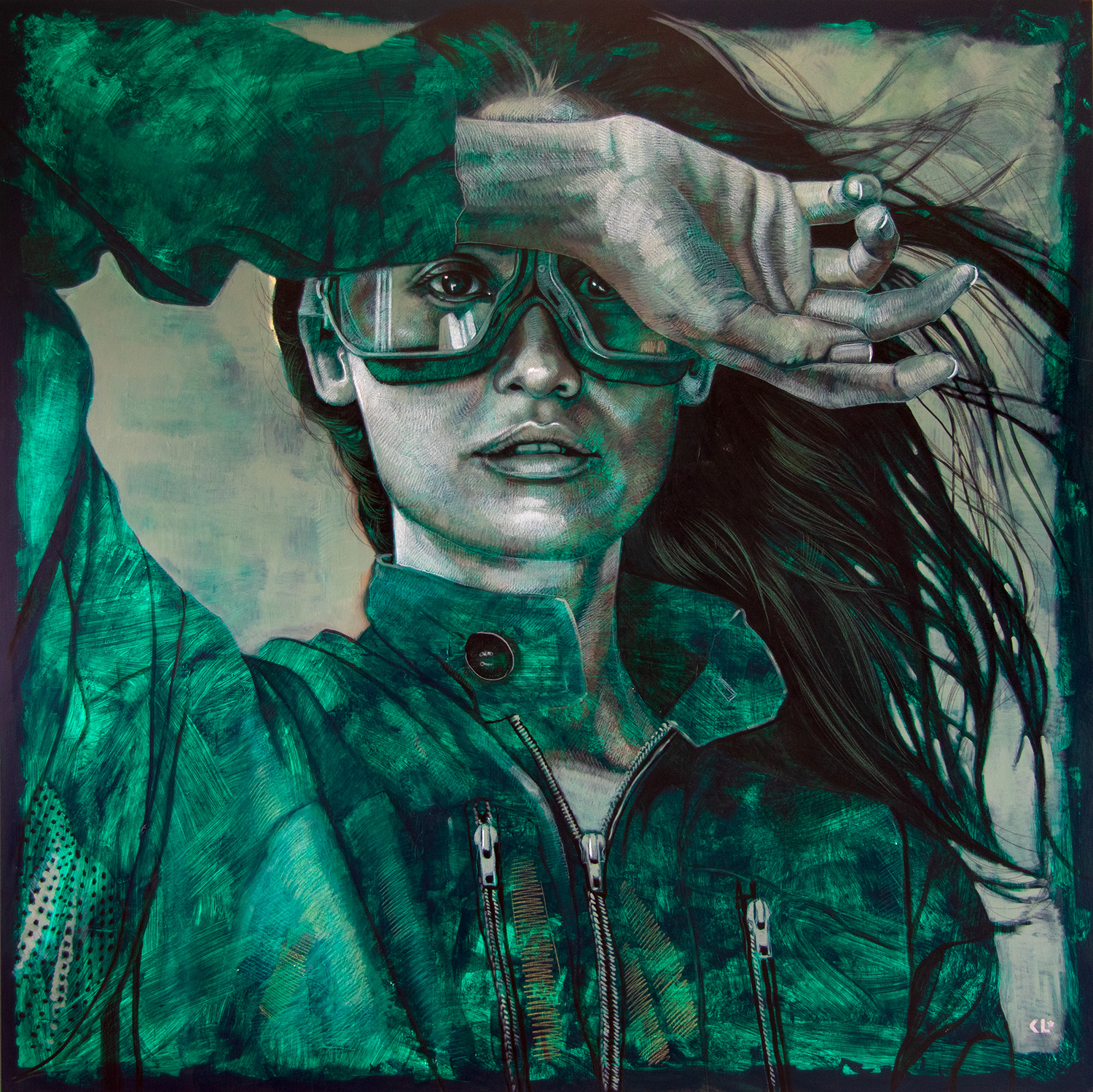

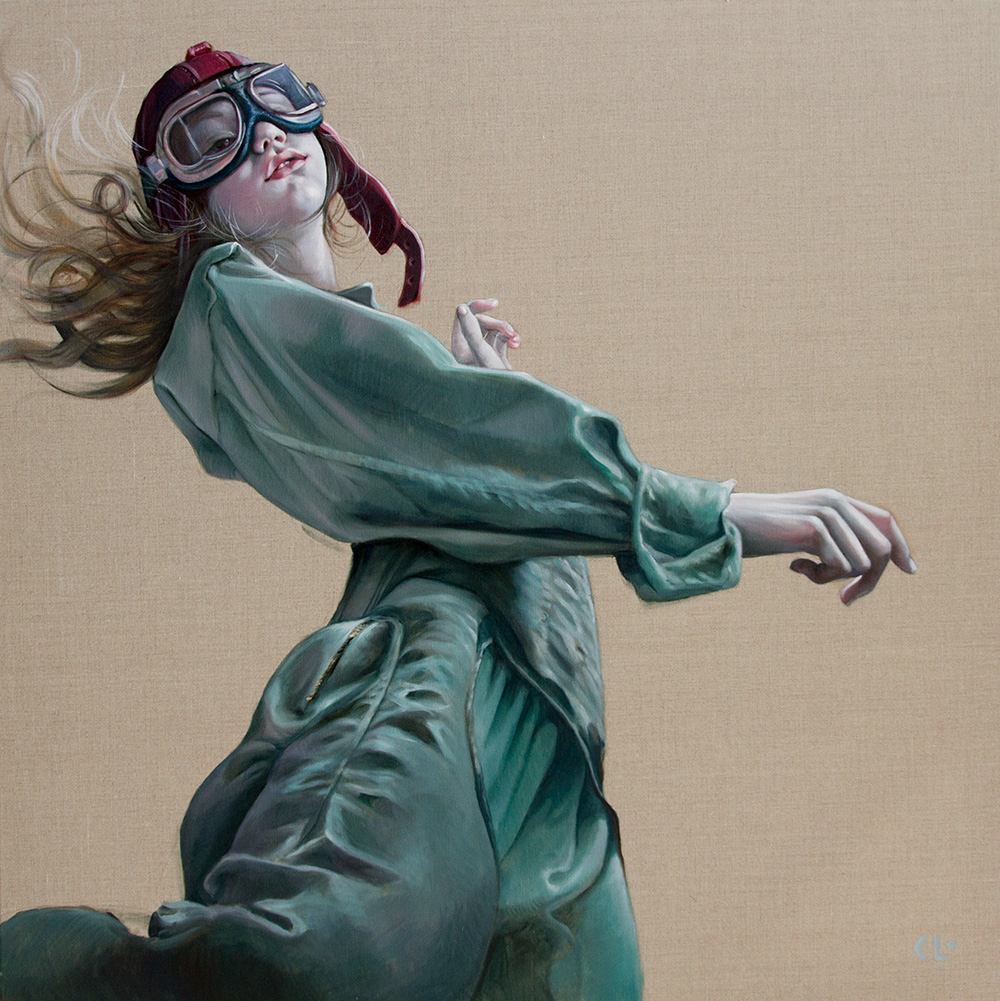

Ruby lips, red lingerie, luminous bare skin, the subjects of Kathrin Longhurst’s paintings provocatively sexualize symbols of communist propaganda. Growing up in East Berlin ‘behind the iron curtain’, Kathrin’s access to glamour was strictly limited, she longed for ‘pretty dresses and pretty things’. Her paintings recall this love of luxuries formerly forbidden, while her female figures challenge varying definitions of feminism through their combination of strength and desirability.

But reclamation of feminine allure in the wake of communist era ideology is only one layer of Longhurst’s work. This recent exhibition continues the exploration of the concepts of propaganda and media, in particular referencing the use of heroes in Eastern European government posters. Longhurst loans signature features of these posters to her subjects, her large scale paintings focusing on a solitary figure towering proudly over us, most often posed before the hammer and sickle flag. The role of the hero was crucial to the success of communism. People needed to identify with the hero or heroine in propaganda to be motivated to continue to serve their country, striving to accomplish the deeds that had elevated that person to heroic status. ‘They would take certain people and turn them into heroes, people that aligned with their ideology’. Military heroes and heroines saturated Longhurst’s education and shaped her childhood ideals. ‘At school, even our history books were different. In maths… we learnt to count with little tanks and soldiers’. When her family fled from Eastern Europe to Sweden, at the age of fifteen Kathrin was forced to assimilate to an entirely new system of beliefs. ‘Everything I had believed to be true was fiction. It was a story… pushing someone else’s agenda. I felt so betrayed – thought, why have you fed me these lies? I was so angry at the media, angry at the lies that had been pushed on me’. Longhurst’s tumultuous experience of extricating herself from communist ideology is echoed by the skillfully captured belligerence in the expressions and poses of her women, who handle the automatic rifles carelessly, wear their uniforms irreverently. ‘I feel liberated using these props because I can freely show these symbols now, make fun of the past, comment on it – I have freedom of speech, of expression now…’

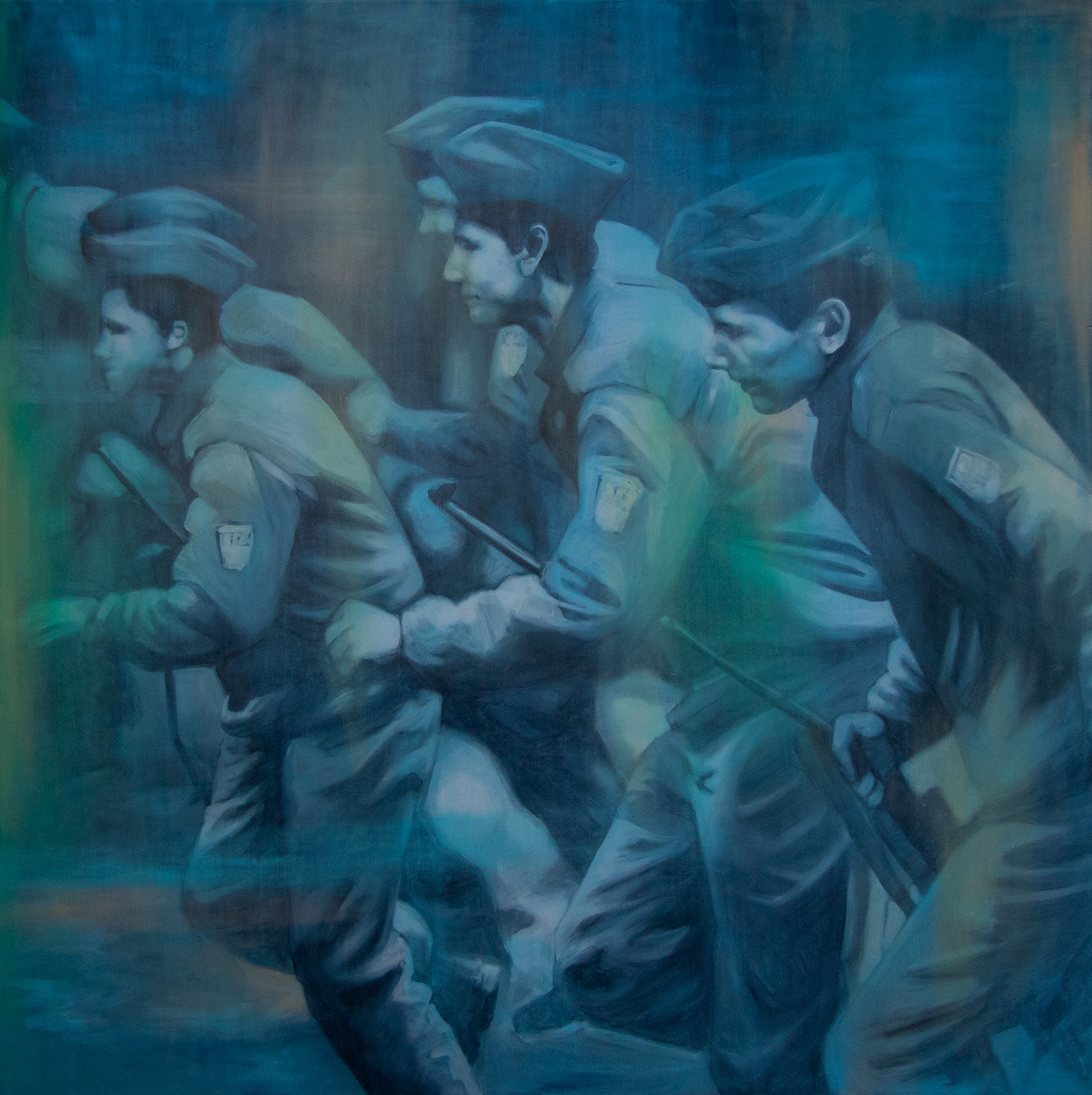

While on the one hand the paintings mimic the depiction of the soviet era women promoted during Longhurst’s childhood, their voluptuous curves and pouting mouths are more reminiscent of 50’s pin up girls than the sturdy peasant ideal presented in socialist realism. A young Longhurst and her friends pored over American fashion magazines smuggled in to East Germany, admiring the models and coveting the fashions. Unable to travel themselves, they took the glossy images as true depictions of American women, of American life. ‘For us it was like a dream world – we assumed that was what the west was like and thought ‘I want some of that’. Longhurst purposefully references American ideals of sexuality, weaving the recognizable communist and more subversive western forms of advertising together. The introduction of male figures in this series casts further light on constructions of gender in the media. Juxtaposed with the confrontational female figures, Longhurst’s boys are gentle, their poses calmer and the typical depictions of the sexes seem reversed. Expanses of bare flesh and the saturated tone of her palate highlight the contradictions and further illustrate her view that ‘propaganda is all around us. It’s not specific to a period of time, a country or a regime…it’s everywhere’.

The narrative backgrounds in these new works display a transition from Longhurst’s previous poster allusions to a more subtle reference to Communist historical paintings. Dramatic lighting and the velvety, sumptuous flag, appearing almost as stage curtains, construct advertising and propaganda references as forms of theatre. In Longhurst’s own words ‘everything depends on who is telling the story’. Expert rendering of facial expressions prevents her subjects from being constrained by the genres she references. As the figures flaunt their overt trappings of sexuality and communism, they address the viewer with a gaze so authentic, objectifying them becomes impossible. This combination of technical proficiency and conceptual depth enable Longhurst to successfully layer varying interpretations of sexuality, themes of freedom and media to create works that are thought provoking, masterfully constructed, beautiful.