Exhibition Essay by Emma Crott

“Children of the Revolution” May 2013

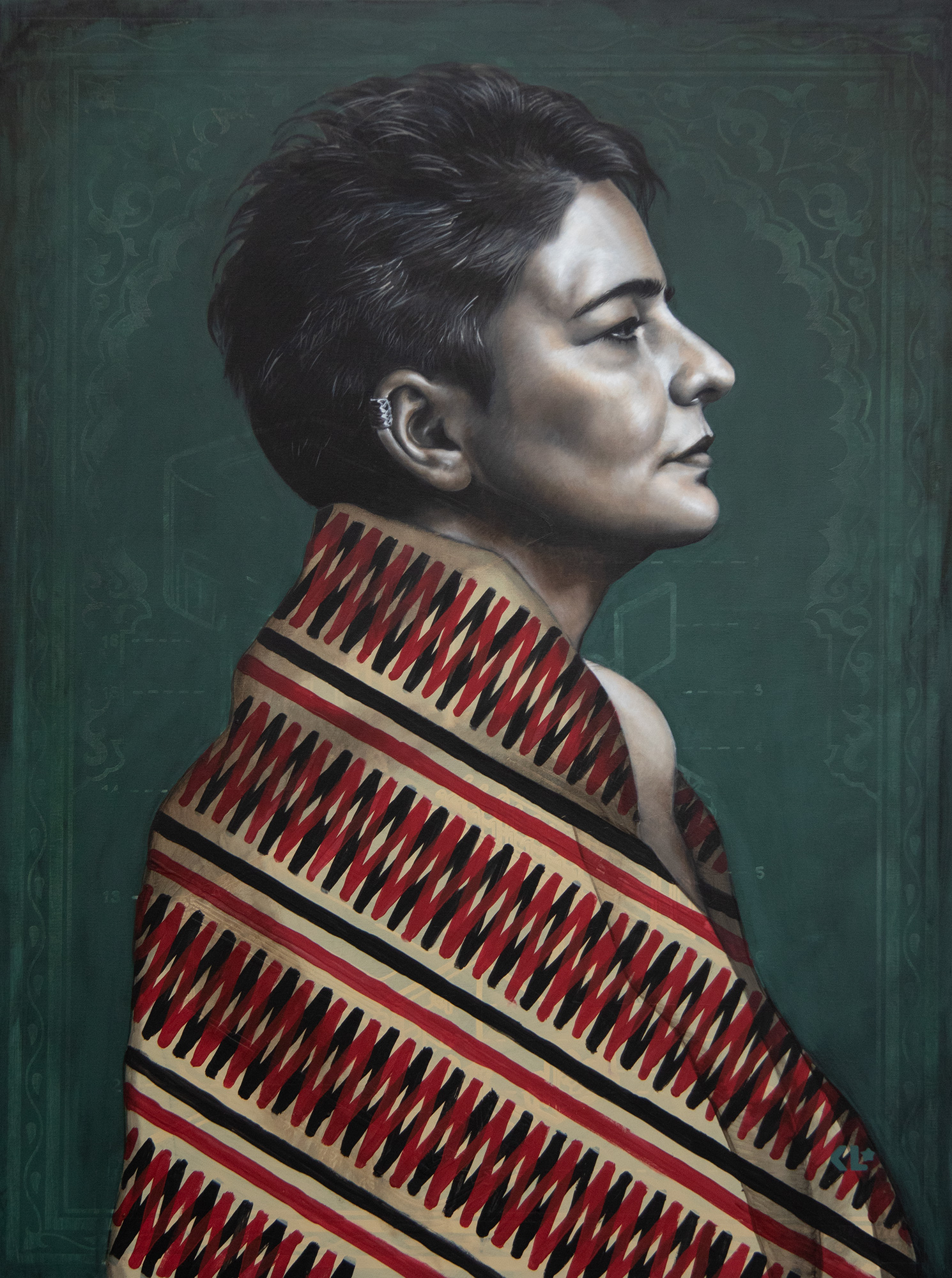

Former Soviet leader Joseph Stalin once declared, “You cannot make a revolution with silk gloves”, yet paradoxically the women featured in Kathrin Longhurst’s recent body of work Children of the Revolution revel in luxury. Their nails are beautifully manicured, their skin pale and unblemished, provocatively pouting their rouge slicked lips – all signs of wealth, opulence and femininity discouraged by early communist regimes.

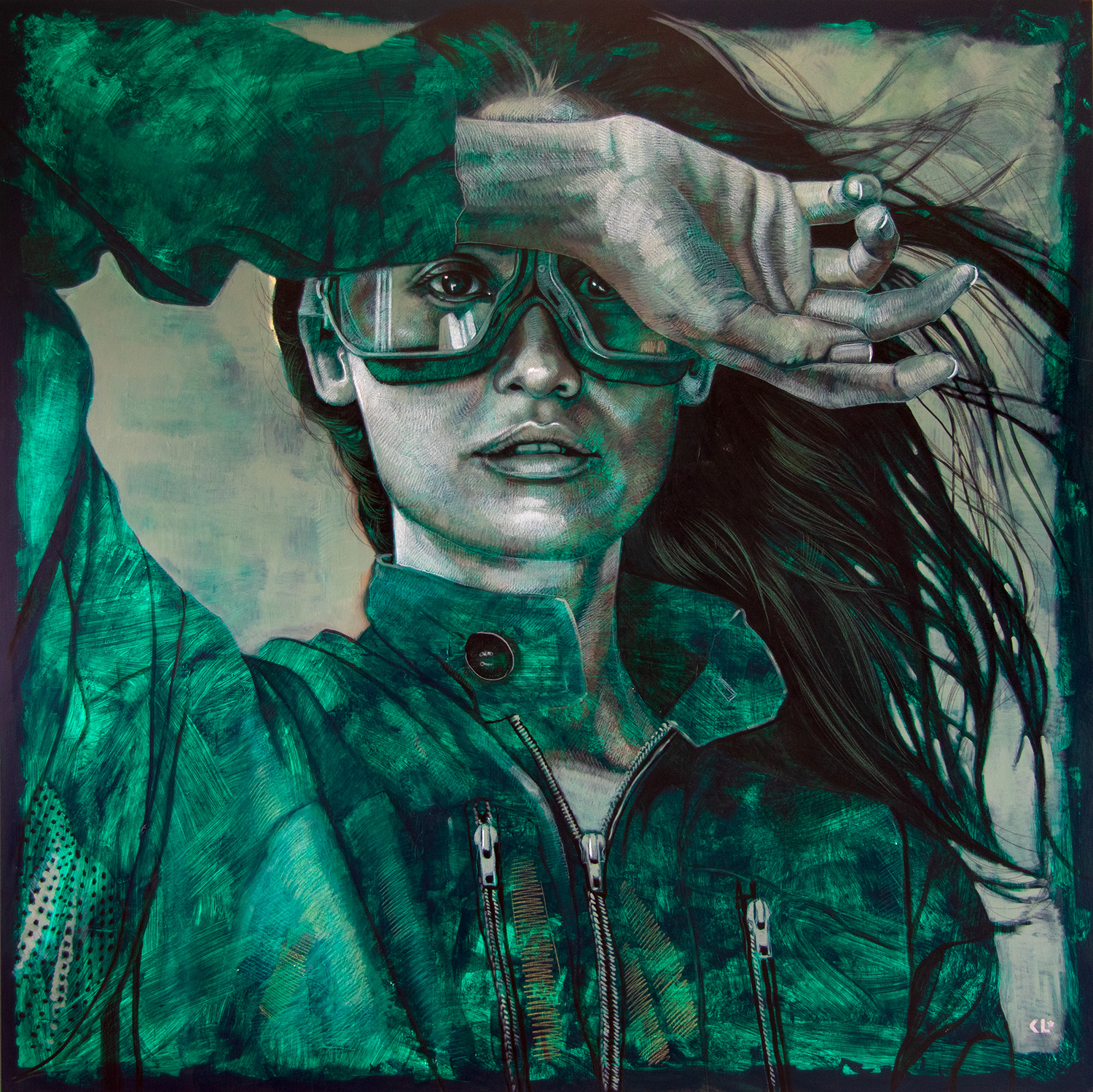

Having spent most of her childhood in East Germany before her family fled to Scandinavia two years before the fall of the Berlin wall, Longhurst is all too familiar with the complexities of socialist ideology and communist propaganda. It was in the German Democratic Republic that she unwittingly consumed a bombardment of imagery portraying strong, fearless women used as ambassadors for the dissemination of political messages and the indoctrination of social adherence. These women, featured in posters, advertisements and often seen at public events, were not only depicted as strong and muscular (the very antithesis of conventional femininity), they were often shown in professions traditionally associated with men such as aviation, military and aeronautics. Longhurst draws on this imagery to form the basis of her powerful series – she depicts women in various types of headgear symbolic of such professions. Yet she infuses these ‘socialist heroines’ with a sexiness and sassiness redolent of 1950’s American pin-up girls.

There is no denying that the Communist party had a profound effect on the opportunities and rights of women in the Soviet Union (and Eastern Europe more generally) – in Children of the Revolution Longhurst specifically references Valentina Tereshkova, the first women in space, and Marina Raskova, the first woman to become a navigator in the Soviet Air Force in 1933. She is particularly interested in the cult status these women attained, something Longhurst compares with the idealisation of ‘rockstars’ in the west. Yet such equality was achieved at a cost – female sexuality and femininity were heavily downplayed. This is particularly obvious in art history with the rise of Socialist Realism in the mid-1920’s, a style opposed to the progressive avant-gardism flourishing in Europe at the time, that instead declared to “depict the present day: the life of the Red Army, the workers, the peasants, the revolutionaries, and the heroes of labour”.1 Women were particularly portrayed as rosy cheeked, stocky workers dressed in ill-fitting, bulky clothing such as the female subject of Aleksandr Deineka’s painting ‘On expanse of Moscow buildings’ (1949).

While Longhurst’s figurative painting style is indebted to Socialist Realism, her female subjects are anything but sexless. The power of her work lies in a carefully balanced juxtaposition of opposing realities: the hint of nakedness, the supple flesh and doe-eye expressions of the women are in stark contrast to the harsh materiality of their headgear. So too is their model-like poses incongruent with the 5-pointed red star repeatedly featured, a common communist symbol used to represent the 5 ‘classes’ of socialist society. The slightly obscured Russian text in the background of many of the works, translated as provocative words such as ‘sassy’, ‘naughty’, ‘snob’ and ‘bitch’ is not only reminiscent of the format for magazine covers but also references the Russian Constructivists who used graphic text alongside abstracted forms and shapes, often imbued with politically charged meaning.

A historically, politically and socially attuned artist, Longhurst employs such visual techniques to explore broader dichotomies such as east/west, masculine/feminine and socialism/capitalism. Not only can the beautifully rendered works in Children of the Revolution be read as a profound satire of communist ideology, Longhurst also seems to be embracing two seemingly conflicting streams of feminism in her work – that where women seek the equal rights and opportunities provided to men by mimicking the qualities and professions typically associated with masculinity, and those who embrace stereotypical notions of femininity as empowering and differentiating.

Children of the Revolution is a series of works that are not only skilfully produced, but also conceptually strong – the proven makings of a truly successful artist. Longhurst herself has commented “I’ve really enjoyed producing this series as it’s allowed me to explore my own cultural heritage” and it is in that history that makes these glamorous, sexy, modern day women all the more powerful.

Emma Crott

PhD Candidate

College of Fine Arts, Paddington

1 The Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia, ‘Declaration’, first published in ‘Exhibition of Studies, Sketches, Drawings and Graphics from the Life and Customs of the Workers’ and Peasants’ Red Army’, Moscow, June-July 1922