Exhibition Essay by Kate McAuley

“We Can Be Heroes” December 2022

During the summer of 1977, while David Bowie was writing and recording his now beloved anthem Heroes in West Berlin, the artist Kathrin Longhurst was spending her childhood on the eastern side of the infamous wall, living under the strictures of a Communist regime and learning her arithmetic using school books illustrated with ballistic missiles.

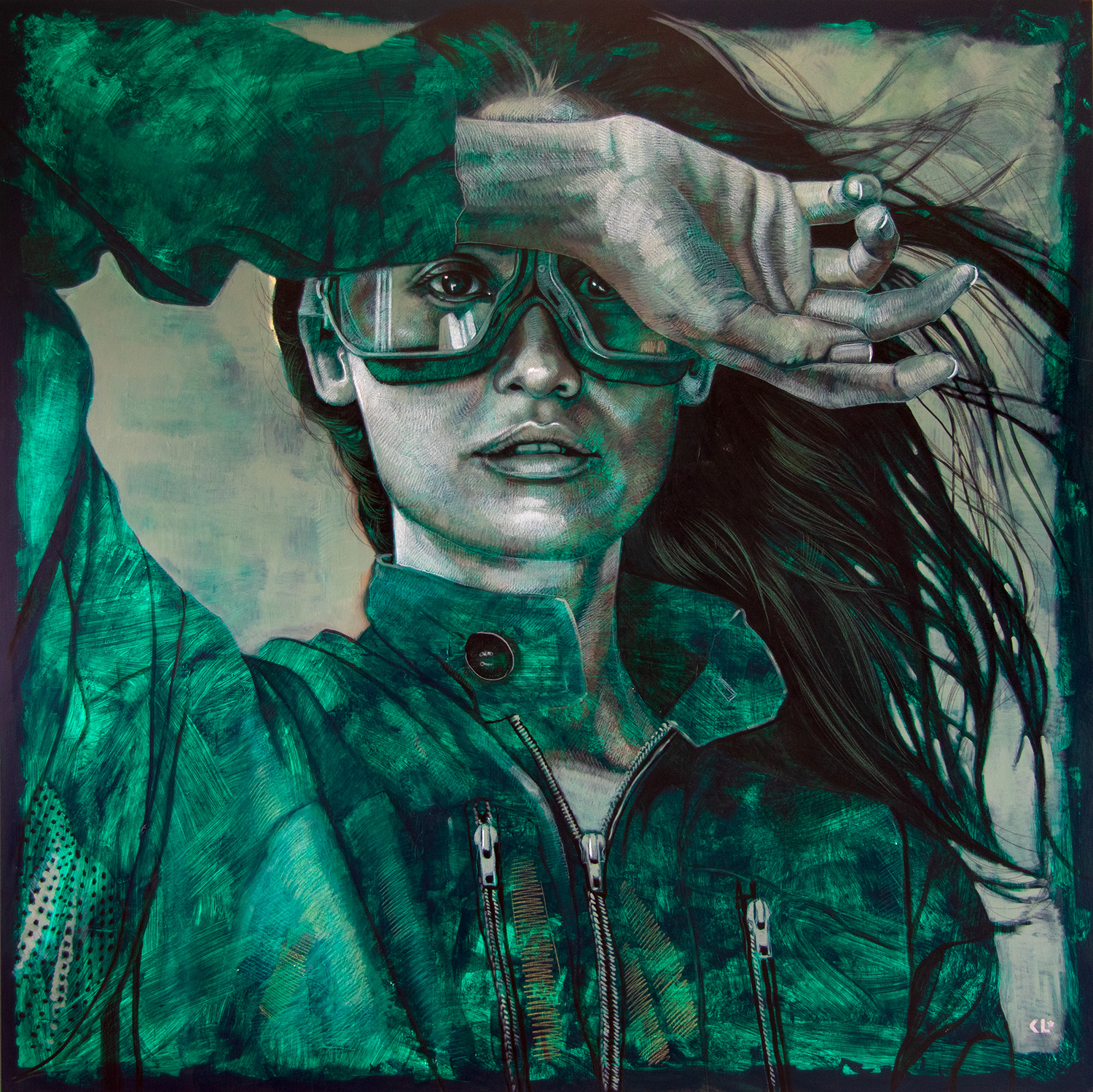

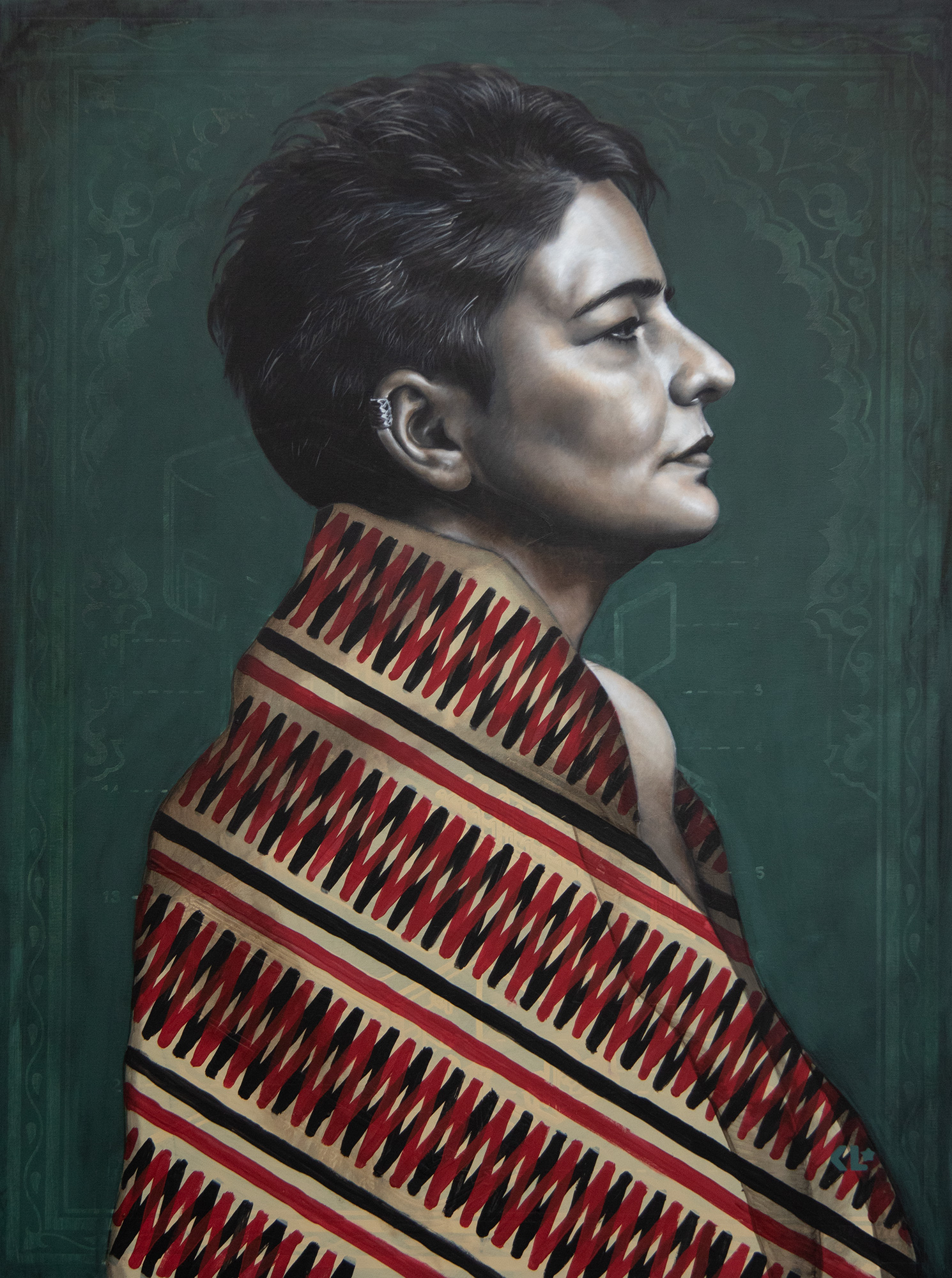

Much has happened for both in the intervening decades: Bowie remains a cultural icon despite his death in 2016, while Longhurst, who fled East Berlin for Sweden in the late 80s, ultimately emigrated to Australia, where she became an award-winning artist and a major champion of the feminist cause. Known for her bold large-scale portraits of charismatic and often defiantly strong women, Longhurst has long challenged the patriarchy and with this exhibition she continues her crusade.

For ‘We Can Be Heroes’ – the title of this body of work and a line taken from the chorus of the aforementioned Bowie classic – the artist conducted a visual thought experiment, recasting her female subjects into the heroic archetypes traditionally associated with the much lauded pursuits of (predominantly white) men. Through the works on display here, Longhurst asks the viewer to question how the world might look for us today if women had historically been given the same opportunities as their male counterparts.

What if the statues raised in our public spaces, the archival footage of amazing feats and the newspaper articles of glorious times past were given as much financial investment, air time and column inches to include all people, regardless of gender? And finally, what if it were women who chronicled who should be lionized and venerated?

To examine how these questions might be answered, Longhurst drew inspiration from historical photographs, particularly of heroic men, taken using the silver collodion (or wet plate) process. Due to long exposure times, and unnatural poses, these time-warn images are both dramatic and evocative of former glories. Instead of masculine exultation, however, we bear witness to powerful female leaders, military commanders, pioneers and explorers.

To achieve such a daring and gritty remit, Longhurst evolved her process from working solely in oils to incorporate a variety of different techniques to great effect. Pencil, charcoal and ink formed part of her canon. She also scraped her canvases with sandpaper and smeared them with red paint to create the illusion of time passing. The result is a powerful representation of what could have been.

It must be acknowledged that gender equality has made significant strides, particularly in recent years, but in a country where there are more statues dedicated to animals than women, we are reminded of how far women still have to go to reach any kind of parity. Representation matters. It feeds into our personal belief systems, how we define what is possible, and promotes the patriarchal status quo. There is no changing history, but by shining a light on this pervasive inequality and reaching back into the past to reimagine a different present, Longhurst reminds us of what needs to change now so that the future can be better for us all.